NOCTURNE

- Christopher Page

Eurydice is the limit of what art can attain; concealed behind a name and covered by a veil, she is the profoundly dark point towards which art, desire, death and the night all seem to lead. She is the instant in which the essence of the night approaches as the other night.

–Maurice Blanchot, The Gaze of Orpheus

Nocturne is a new body of pictures Christopher Page has produced under very particular circumstances.

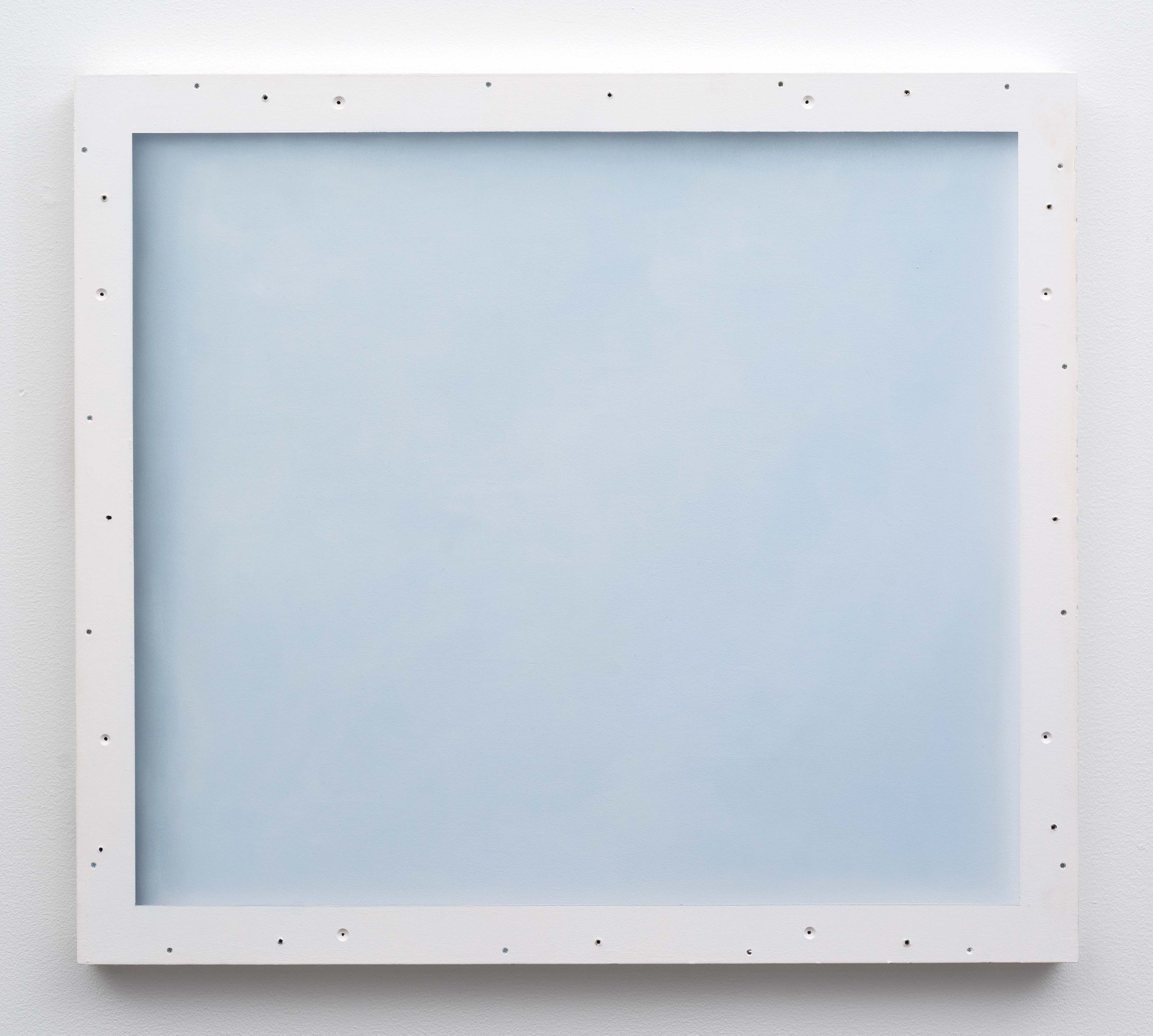

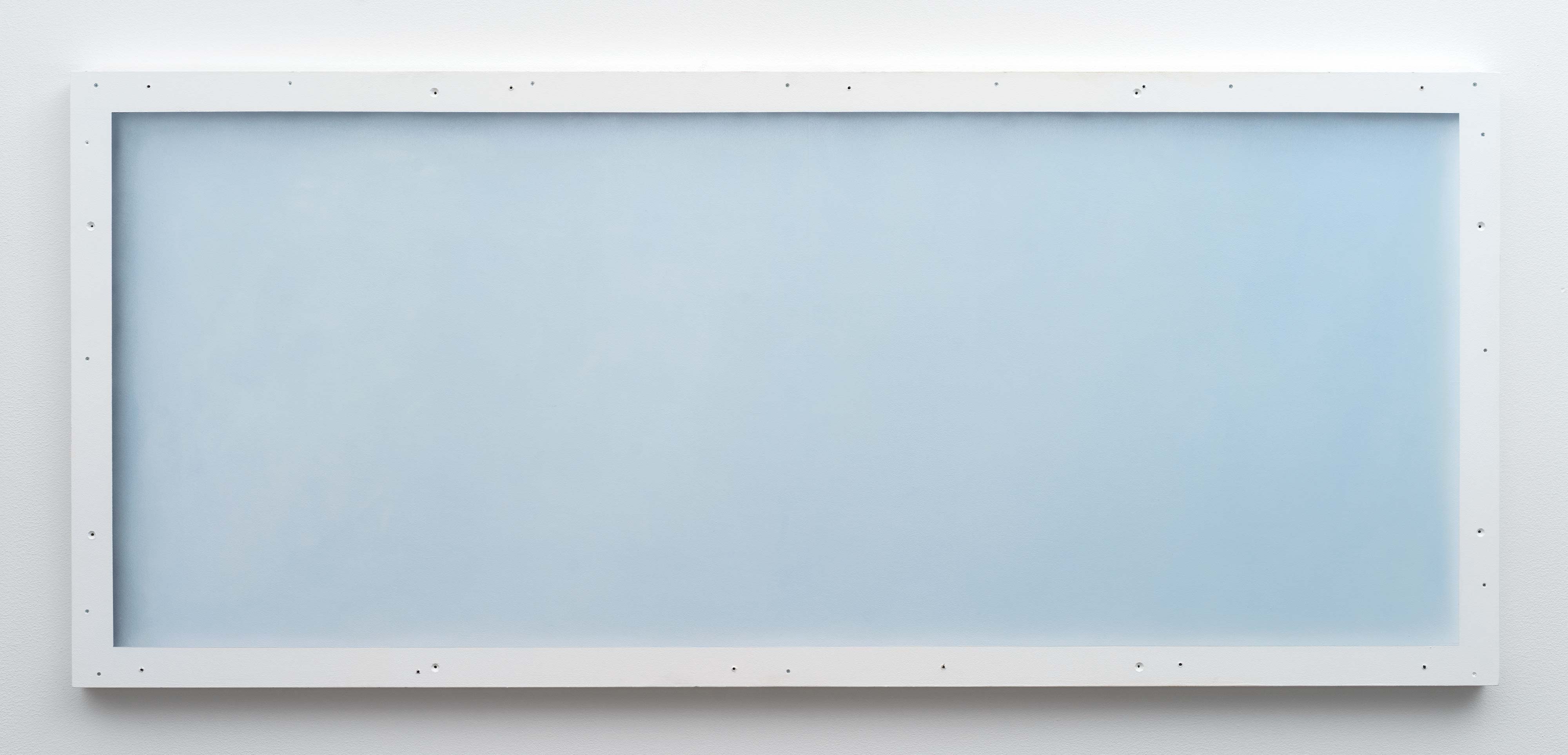

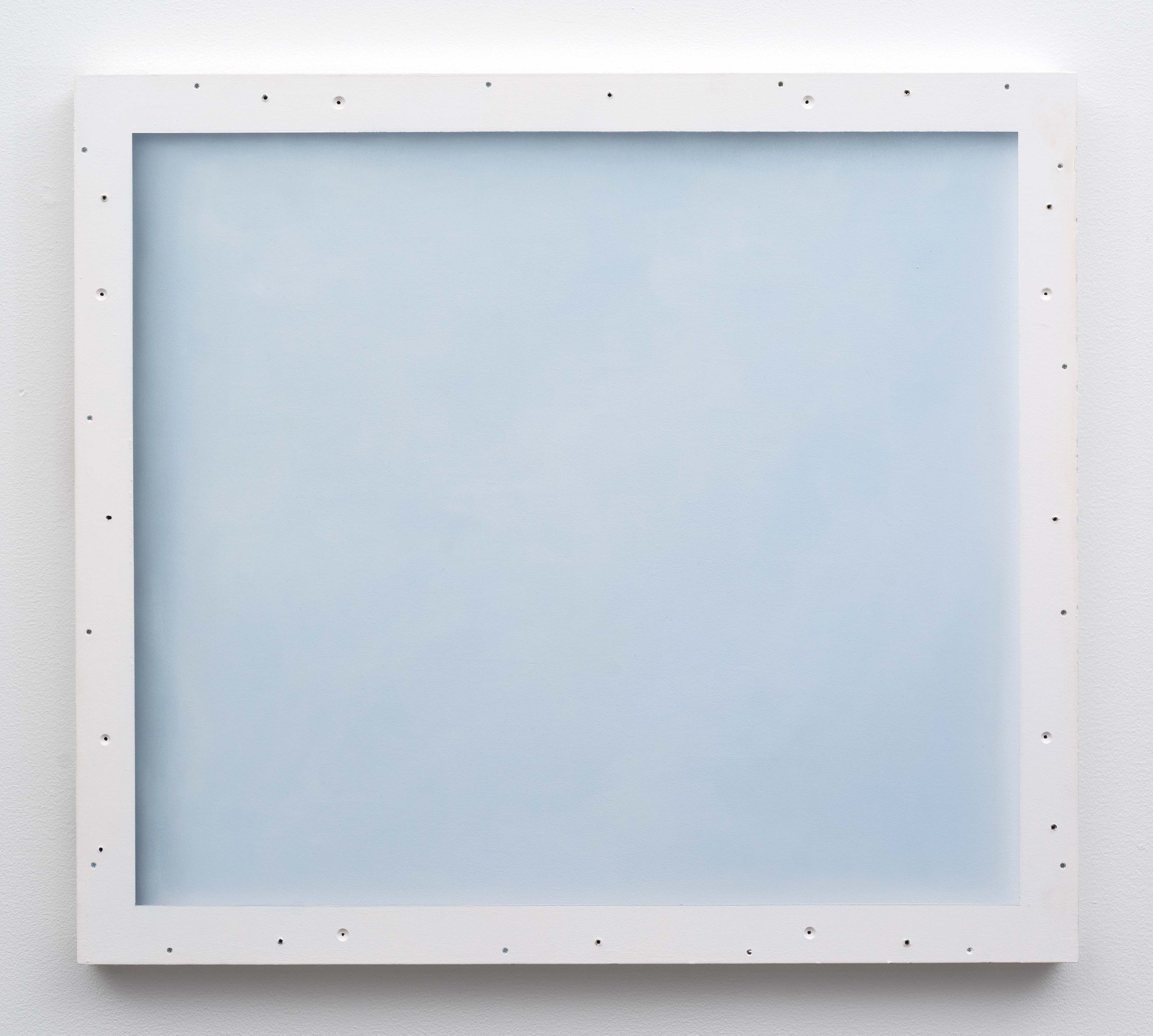

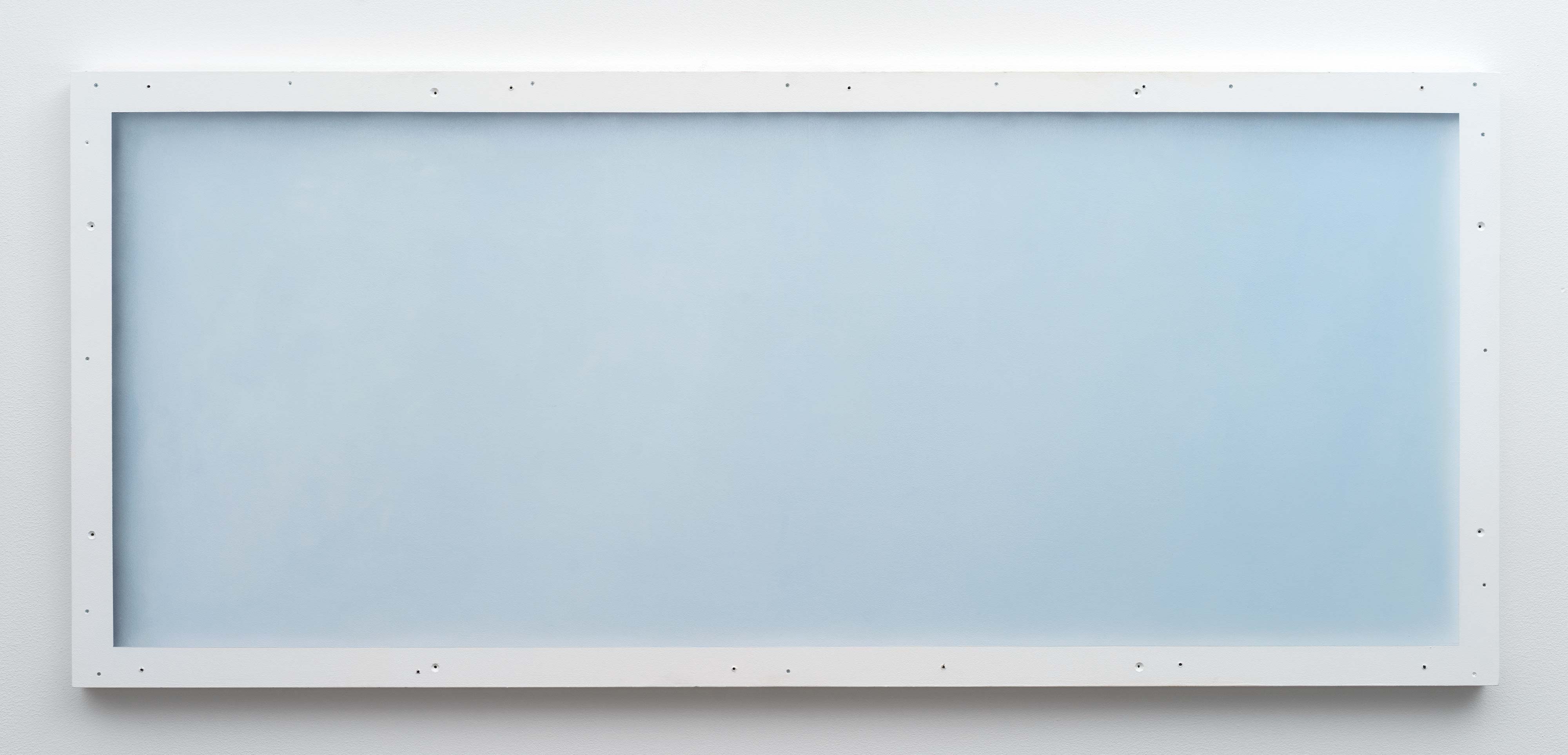

The first work in this exhibition is a long movement of 12 panel-pictures - akin to a processional frieze - that, when screwed together, forms its own shipping crates. When assembled the 12 units become 2 crates (6 panels each), which are the proportions of a (20 ft) shipping container, scaled down.

This work has been on a long migration before arriving at Lord Ludd. The first stage of manufacture (the fabrication of the panels, the painting of their /cloudy/ faces*) was completed in Athens, Greece, where Page lives and works. From there the pictures - as crates - have been hauled, personally by the artist (with the help of many others), on a container ship across the ocean to New York, as part of an artist residency. While on board, Page coated the crates in the ship’s white marine paint to protect them on their journey. And when finally installed in the gallery the finishing shadows and highlights were added with reference to light sources in the space, making the works at home in their temporary accommodation.

The paintings are unstable and contradictory. The /cloud/ layer was painted systematically - black and white paint applied in blotches (to different degrees between panels) in one pass and blurred together - giving them the quality of a digital 'texture', but an effect of deep space none-the-less. The airbrushed over-layer of shadow and highlight imposes a contradictory shallowness on the pictures. On the edges of the panels screw holes and markings refer to the reconstruction of the crates; on the wall these become hieroglyphic.

The wall paintings on display in this exhibition are also a movement. Seen as a series, this arrangement is itself a kind of migration from framed space to the spacialized frame, knotted around itself. These works draw on, and play out, the knotted registers Jacques Lacan names as the ‘Imaginary’ - the realm of images that, mirror-like, sustains our sense of individuality - and the ‘Symbolic’ - the impersonal structures, like language, in which we are embedded and through which we are constructed.

In sum, these works are passages through structures, whether material or ideal. The problem, indeed paradox, they turn to face is how structure becomes a picture. They offer no simple representation because these pictures are incantations of the gap that is representation, what Blanchot calls "the other night."

To paint in a Nocturnal key is to call to mind the Romantic musical form that evokes the Night for melancholic effect. The dislocated quality of these works might seem to run counter to such sensual evocation. But ‘Romantic’ was also Hegel’s term for the period in art history which finds art de-centred, implicated in systems beyond itself, in its twilight. Today, in the "bad infinity" of the Contemporary, twilight is banished. And so the Night provisionally and implausibly evoked here is the invisible, unrepresentable obverse of the eternal daytime that clouds our world.

*The denotation /cloud/ is used here in the same way as Hubert Damisch does in his book Theory of /Cloud/. The /.../ is used to direct attention to the signifier and not the signified, i.e. to the word cloud itself or a /cloud/ form in a painting, and not to a cloud in the sky.

Christopher Page (b. 1984, London) lives and works in Athens, Greece. Page received his MFA in Painting and Printmaking from the School of Art at Yale University and his BA at Central St Martin’s College of Art and Design. Recent solo exhibitions include Dawn at Hunter/Whitfield, London and Pictures at Sushi Bar Gallery, New York. Recent residences include Instituto Inclusartiz in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

christopherorlandopage.com

Night

by Orlando Reade

The night, once thought to be a natural entity, has started to mutate. This essay presents three pictures of the night that witness its mutation in the Western world.

1

One afternoon last April I was waiting for a train when a man asked me for a dollar. His speech was slurred, his mouth open, his eyes raised, as if in an expression of ecstasy. He was leaning to one side, as if against an invisible wall. I didn’t give him a dollar, I got on the train. When the train was due to leave a woman in the uniform of New Jersey Transit announced that there was police activity at Roebling, one of the stations on the River Line, the light railway that cuts down through the central part of the state, so the train was going to stop at Bordentown, the station before Roebling, and we were all going to get on a bus that would take us to Florence, the next station along. At Bordentown the train decanted its passengers before returning to Trenton, and we waited at the end of the platform for the bus. Some people looked unhappy, some were complaining, some complaining – it seemed – for the pleasure of being in this predicament together. At the end of the platform were two metal poles: on top of one, an image of the railway bridge at Trenton with its famous inscription: Trenton Makes The World Takes; on top of the other, an elephant with a castle on its back, standing on an arrow that pointed west. The man with the slurred speech was standing by the poles. He approached a woman and asked when the bus was coming. I have an appointment at ten, he said, is it ten? The woman said to him it’s four. Commentary: The mutation of night was a consequence of industrialization, as one commentator in the nineteenth century recognized: “The variation of the working day fluctuates, therefore, within physical and social bounds. But both these limiting conditions are of a very elastic nature, and allow the greatest latitude.” The logic of work in the modern world has pushed the day towards an absolute limit.

2

In the Yuriev monastery there is an icon of the Trinity in which the Father appears with the Son sitting on his lap. The Father, august with white hair and white robes, is seated on an orange throne, his feet splayed on an orange pillow. On the right hand of the Father, the third finger is pressed together with the thumb, which is arched so that its curvature runs up against the halo of the Son, as if removing an errant hair from its gilded edge. The Father’s left hand holds a scroll loosely, so that he appears to be absent-mindedly stroking the left side of the Son’s halo. The robes of the Son are the same orange as the throne, tiny in comparison to the robes of the Father but swelling voluptuously over his knees, modestly gathered where his heels touch. On the sandals of the Son four brown leather straps join at the point where the nails would be punched through. Something is sitting in the lap of the Son, which he holds with both hands like a large and delicate toy. It is a sphere, with rings of white and grey, and a black circle at the center. A white bird emerges from the blackness, with the faint trace of a halo, its wings stretched for flight. Commentary: Representations of God the Father are common in Orthodox iconography. This represents a strange contradiction, since God is personified in Christ. It may therefore be heretical to represent God alongside Christ. The scholar Father Steve Bigham has suggested that, in order to avoid heresy, the Father of this icon should be understood as a personification of the idea of fatherhood. The anthropomorphic idea of God is a failure of human knowledge. But it is difficult not to imagine the white man in this icon to be a representation of God. This potentially unacceptable image of God reveals a set of laws for representation: (1) the body of the Father is inconceivable; (2) the Father sees everything; (3) the Father’s absence is the structural principle of all that is visible. If the small black circle at the center of this picture is night, it is contained in the eternal day of God the Father and his sacred bureaucracy.

3

A poem by the Welsh mystic Henry Vaughan, speaks of a divine night that the poet has not himself experienced but has heard about.

There is in God (some say)

A deep, but dazling darkness; As men here Say it is late and dusky, because they

See not all clear;

O for that night! where I in him Might live invisible and dim.

Commentary: Vaughan is hesitant to introduce the idea of God’s darkness, admitting that it rests

on less than certain evidence. It may only be a metaphor, used by theologians to communicate the divine being or the non-being of the divine. The poet allows himself only to report what “some say” but doesn’t identify his sources. Then he reports what is said of night by “men here,” who give to night the negative attributes, “late and dusky,” because they can only understand it as the absence of day. But there is this other night that cannot be named, a night of “deep, but dazling darkness”. This is not a negative theology (a belief that God is unknowable, or is the unknowable): with the useful word “that, the poet points to what he cannot name. This night is not to be taken as a metaphor for death; Vaughan wants to enter and inhabit it. It is not a wish to return to the womb but to be born again in the refuge of the father. The poem concludes with an exclamation, a sign for the reader to make a dark circle with their mouth—a sigh of ecstasy. The symbol, “O,” is a figure that corresponds to the closed world of the late medieval church and at the same time it is an opening towards the infinite universe, an idea comprehended by mystical experience long before it was formalized by mathematical science. Without deciding about the scriptural authority of “that night,” the poet calls for it. The poem leaves behind the objects of everyday experience and steps out into an invisible world.

Coda: Vaughan’s passionate address to the night anticipates the sublime experience of Romanticism, which emerged in Europe a century later. The Romantic subject, structured by the rationalizing imperatives of Enlightenment philosophy and European imperialism, found in Nature (as Vaughan found in God) an encounter with something that could not be captured by scientific thought. In the Romantic scene, a solitary figure calls out from the fortress of reason into the night, dying to be transformed. But this scene has become a joke. In this world, where reason is a mask for chauvinism and fantasies of transformation are either ridiculed or sold for profit, the day continues to expand. And yet some night remains where we cannot help but escape into.

Orlando Reade is writing a PhD on English poetry and philosophy in the seventeenth century.

Performance

On June 18, 2016, Lord Ludd hosted a solo performance by Ches Smith on the occasion of Christopher Page's exhibition Nocturne.

Ches Smith is an American musician whose primary instruments are drums, percussion, and vibraphone. He writes and performs music in a wide variety of contexts, including solo percussion, experimental rock bands, and small and large jazz ensembles. In September, Smith will be in residence at The Stone in New York, a performance space dedicated to the experimental and avant-garde music. Smith has performed with Good For Cows, Marc Ribot, Theory of Ruin, Mr. Bungle, Secret Chiefs 3, Xiu Xiu, Trevor Dunn's Trio-Convulsant, Carla Bozulich, Beat Circus, Sean Hayes, Ben Goldberg, 7 Year Rabbit Cycle, Ara Anderson and Fred Frith. He has also recorded and performed a full-length album of his own solo percussion pieces entitled Congs For Brums (2006). In 2010 he released Congs for Brums 'Noise to Men'.

chessmith.com

| Artist | Title | Year | Medium | Dimensions | ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (I) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (II) | 2016 | Oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (III) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (IV) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 26.6 in (60 x 67.6 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (V) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (VI) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (VII) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 26.6 in (60 x 67.6 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (VII) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Noctunre (IX) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Nocturne (X) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 26.6 in (60 x 67.6 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | High Noon (I) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 26.6 in (60 x 67.6 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | High Noon (II) | 2016 | oil and acrylic on panel | 23.6 x 54.3 in (60 x 138 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Schema S-16 | 2016 | acrylic | 23.875 x 21.25 in (60.6 x 54 cm) | |

|

Christopher Page | Dyad | 2016 | acrylic | 23.6 x 18.5 in (60 x 47 cm) |